How Climate Change is Affecting the Alps

One hundred years ago, the first passengers were making their way from Chamonix Valley to the Mer de Glace on the Montenvers cog railway. Tourists were drawn from all over the world to see the mysterious “sea of ice” with their own eyes.

While the glacier continues to attract visitors, it is diminishing in size at an astonishing rate. When the Montenvers Hotel was built in 1880, guests could stroll out of the hotel and reach the glacier in a few steps. Today, the Mer de Glace is receding at a rate of 4 meters a year. A gondola ride and 367 steps are now required to reach it.

Let’s explore how the climate is changing in the Alps and the consequences of these changes for the landscape, wildlife and local populations. To learn more about Run the Alps’ sustainability efforts, click here.

How is the climate changing in the Alps?

When we talk about climate change in the Alps, we are referring to two key variables of the climate: temperature and precipitation patterns.

Temperature

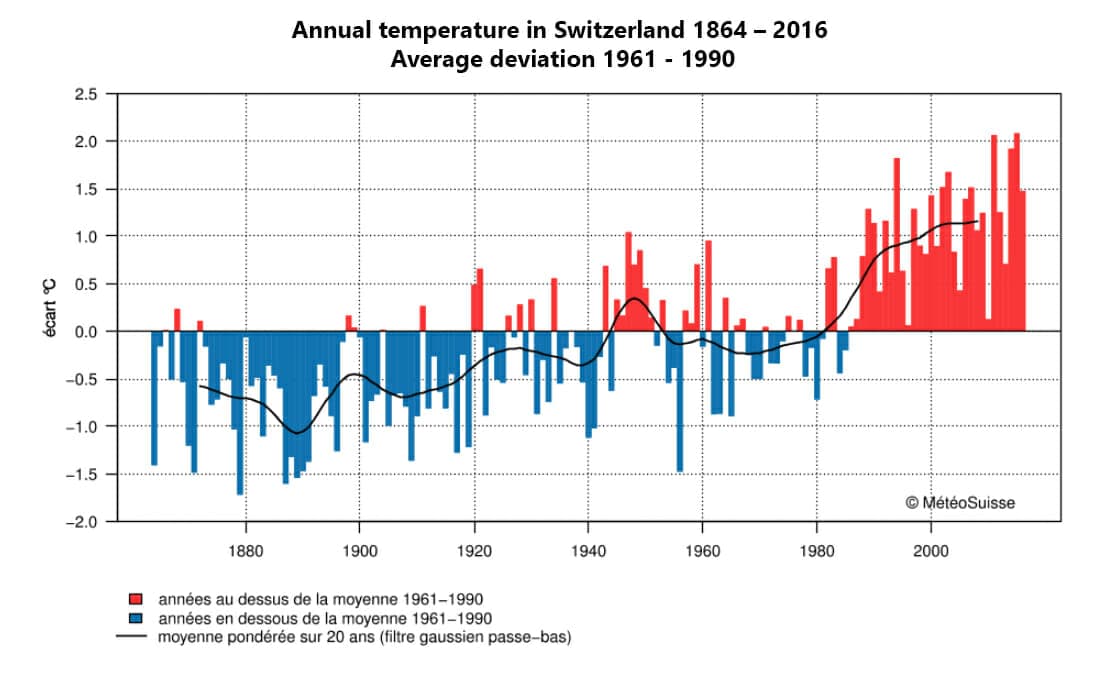

While temperatures have risen by 2.5°F (1.4°C) in France over the 20th century, they have risen by 3.6°F (2°C) in the European Alps. Warming is amplified in mountainous regions because as snow cover melts, it reveals dark rocks which absorb more of the sun’s rays. Year-on-year warming is becoming the trend with sixteen of the seventeen last years being the hottest on record [1].

Climate change also increases the frequency of extreme weather events such as heat waves. By 2100, it’s predicted that every other summer could be as hot as the European heatwave of 2003, which saw the highest temperatures on record since 1540 [1].

Precipitation

The effect of climate change on precipitation varies regionally. Globally, precipitation amounts have not changed much, but in the Alps, we are experiencing increasing instances of drought and less snow cover [1].

“Precipitation patterns are incredibly localized. Climate models are showing that on the French side of Mont Blanc, there won’t be significant changes in the amount of precipitation, whereas the Italian side will experience a decrease. However, it’s not just the amount of precipitation that is important, but whether it falls as snow or rain.

Warmer winter temperatures mean that the middle mountains are receiving more rain, instead of snow during winter. Because of reduced snowfall and warmer spring temperatures, the period of snow cover at mid-elevations has decreased by a month since 1979. This is impacting low-elevation ski resorts who are diversifying into other mountain sports or investing in snow-making equipment.

Snow cover is important because it keeps the water stocked and melting through the season for the valley. Last Autumn I ran up to the Plan d’Aiguille hut in Chamonix and there was no water available. The guardian told me it was the first time he had ever seen the water dry out so early in the season.” — CREA, Mont Blanc

What are the consequences of climate change in the Alps?

What do increasing temperatures and a decrease in snowfall mean for the Alps? The main consequences are glacial retreat, species migration, changing seasonal cycles of plants and animals and increasing instance of rock fall.

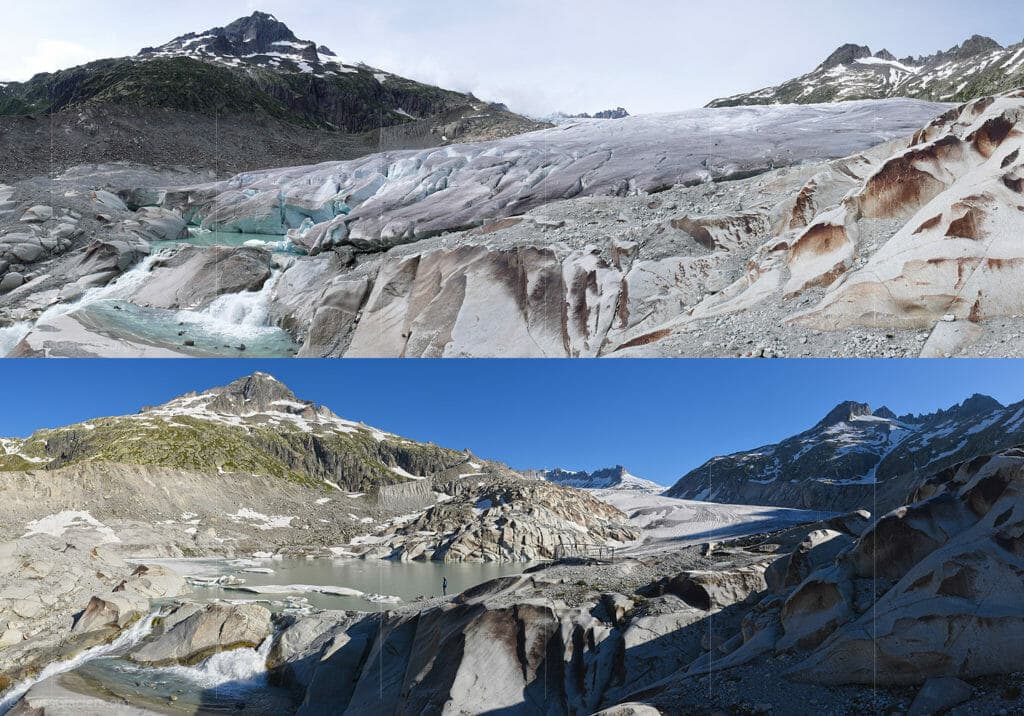

Glacial Retreat

Glaciers have lost half of their volume since 1900 and the rate of retreat is accelerating, with 20% of their volume disappearing since 1980 alone [2]. Unfortunately, even if we make a concerted effort to slow down climate change, even best-case scenarios show that by 2100 most glaciers across the Alps will have disappeared [3].

“Glaciers in the European Alps and their recent evolution are some of the clearest indicators of the ongoing changes in climate. The future of these glaciers is indeed at risk, but there is still a possibility to limit their future losses.” [3]

–Daniel Farinotti, Glaciologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Zurich

Glaciers are not only a visually spectacular part of the landscape, they are the largest reservoir of freshwater on earth and hold more water than lakes, soils, rivers and plants combined [2].

Glaciers store water during wet, cold months and release it when needed in the drier, hotter summer months. Without glaciers, rivers will reduce in flow and it’s likely that small streams will dry up all together. This will have an impact on alpine flora, fauna and agriculture.

Just two years ago, Switzerland experienced its lowest rainfall in almost a century. The drought was so bad that the organization Swiss Mountain Aid had to transport water by truck and helicopter to mountain pastures for grazing dairy cows [4]. Dairy cows need up to 100 liters of water a day in the summer. While we still have glaciers in the Alps, we can afford such costly uses of water, but it’s questionable whether traditional methods of farming will continue to be sustainable in the long term.

Species Migration

As temperatures increase and glaciers retreat, invasive and colonizing species will do well, whereas alpine species will steadily lose habitat until they eventually disappear.

Alpine flora and fauna are called “glacial relics.” They evolved to survive in conditions from the last glacial period. When the glaciers began to retreat around 10,000 years ago, alpine species retreated with the glaciers to mountain regions.

Increasing temperatures and the rising elevation of snow cover mean that emblematic alpine species such as the ptarmigan and mountain hare are being forced higher and higher up the mountains. The ptarmigan is at risk of losing 60% of its habitat by 2050 and could be extinct by 2090 [5]. It’s not only animals that are migrating upwards, though. Alpine flowers are also being forced to migrate and the question is whether they can keep pace with the rapid rate of change.

“The glacier buttercup (*Ranunculus glacialis*) which is specifically adapted for growing in high mountain environments will have to climb 1,200m (3,937ft) by 2100 to find favorable climatic conditions.” [1]

— CREA, Mont Blanc

Trees are taking advantage of the new habitat available to them and observations show that the tree line is rising in the Alps. Unless this is managed in the future, it’s possible to imagine a time when the famous balcony trails of the Alps have their views obstructed by forest.

Seasonal Cycles

Spring came early to the Chamonix valley this year, with a spell of two weeks of t-shirt ski touring weather in February. Early season warm-ups like this are becoming increasingly common, which is changing the seasonal cycle of plant and animal species.

After weeks of glorious sunshine, it came as a surprise when half a meter of snow fell in April and the valley floor was blanketed yet again. The local saying, “Don’t take your snow tires off until May,” reminds us that it’s not the late season snow fall that is unusual, but the lack of it.

As part of their Phenoclim project, CREA Mont Blanc is monitoring common tree and bird species to see whether their seasonal patterns are being affected by climate change. While it’s too soon to draw any firm conclusions, it does seem that trees are beginning to flower earlier, and birds are breeding earlier. On one hand, it increases their growing season, but on the other hand they can be penalized for breeding or flowering early if the cold weather snaps back. Mortality rates for the coal tit bird, for example, are much higher when they begin laying earlier in the season [6].

Reduction of permafrost and increase in rock fall

In 1973, the celebrated alpinist, Gaston Rébuffat, collected the 100 finest climbing routes of the Alps into a beautiful book that is found on the coffee table of every alpine chalet. Just over 35 years later, three of these routes have completely collapsed and a third are completely unclimbable in summer due to the increased risk of rock fall. The remaining sixty percent of the routes have changed drastically due to recession of glaciers and/or rockfall [7].

While it is a natural for mountains to erode and collapse over time, huge rock falls are becoming increasingly common in the Alps due to melting permafrost. Permafrost is permanently frozen ground (soil, rock and ice) that has remained at or below freezing for more than two years. It is widespread in the Arctic and high mountain environments. Permafrost is the “glue” that holds the mountains in the Alps together — and rising temperatures are causing it to thaw out, often with dramatic consequences.

“The [rock] falls occur during the warmest periods or at the end of them. The permafrost is the triggering factor. The global warming [of] +2.C in Chamonix since 1936 will increase the phenomenon. Most probably rock falls high in our mountains will occur more frequently and be bigger according to the increase of temperatures, even during the colder seasons”. [8]

–Ludovic Ravanel, Geomorphologist and High Mountain Guide

The summer of 2003 was so warm in the Alps that rock avalanches happened everywhere. The normal route up Mont Blanc was closed to climbers due to the high risk of rockfall, and 90 alpinists had to be rescued from the Matterhorn due to 1,000 cubic meters of rock collapsing from the summit [8].

“In the summer of 2003 one of the world’s most iconic climbs, the 1938 route on the Eiger’s north face, became yet another victim of climate change. Climbers were shocked to find that there was barely any ice left on the route. The huge second ice field, the third ice field and the White Spider had melted away and now consisted of rubble-strewn rock slopes dusted by blackened snow and pocked by forlorn patches of ancient grey ice. The heat wave of last year, reported to have been the hottest Alpine summer in 200 years, seemed to have finished off this venerable climb.” [9]

— Joe Simpson, Alpinist and author of Touching the Void

Unfortunately, rock fall events have become increasingly common since 2003, leading to mountain closures on Mont Blanc in 2013, 2015, 2017 and 2018 [10]. However, it’s not only alpinists who are affected. Rock fall also puts towns, roads and ski infrastructure at risk. Scientists have drilled a series of bore holes across the Alps to monitor suspect mountains closely, particularly those above settlements [11].

Summary

While exact predictions are impossible, it’s clear that the Alps are entering a period of unprecedented change. Over the next few generations climate change will alter the alpine ecosystem and there will be clear winners and losers. While alpine species will lose significant areas of habitat, colonizers, invasive species and forests will expand their territories.

Local populations will come under increasing pressure from water shortages, rock fall and severe weather events. Alpine resorts will have to diversify to adapt to a future with limited ski seasons and many lower level resorts may disappear altogether.

Governments will be faced with important questions as to how to manage the impact of climate change. Will they continue investing in snow-making technology or choose to diversify their winter industry? Will they manage encroaching forests and continue to subsidise Alpine farmers to maintain the cultural landscape and traditions of the Alps?

As individuals, we have an important role to play in mitigating climate change. The decisions we make regarding how we travel, the food we eat, and what we buy all have an important impact.

Companies must also take their share of the responsibility. In our next article we will explore the environmental impact of Run the Alps trips and calculate the greenhouse gas footprint of our guests. By knowing our impact, we can mitigate it and protect this area we all care about so much.

To learn more about Run the Alps’ sustainability efforts, click here.

Sources

[1] Climate Change and its impact in the Alps (CREA Mont Blanc)

[2] Climate change taking big bite out of alpine glaciers (Deutche Welle)

[3] More than 90% of glacier volume in the Alps could be lost by 2100 (European Geosciences Union)

[4] Drought-affected Alpine pastures get emergency help (Swissinfo.ch)

[5] Un avenir incertain pour le lagopède alpin (Brad Carlson, CREA Mont Blanc)

[6] Phénoclim (phenoclim.org/fr)

[7] Mont-Blanc : les 100 plus belles courses défigurées (Le Dauphine)

[8] The Fall of the Alps (Summit Post)

[9] The Melting Mountains (Joe Simpson, The Independent Online)

[10] Mont Blanc’s Gouter route at risk of closure. Heatwave increases risk of rockfall in Grand Couloir (Brian Kieran, Chamonet)

[11] Melting Permafrost Threatens Alps (Paul Brown, The Guardian)