After the Crowds: Fall Trail Racing in the Alps and Trail Dents-du-Midi, the Oldest Trail Race in Europe

It’s fall in the Alps. The green pastures of a Switzerland summer have turned shades of brown and red. US trail runners have, for the most part, packed up their Salomons, Hokas, and Sportivas and headed for their homes in the New World. With the internationally-flavored alphabet soup of races like UTMB, CCC, and OCC behind them, mountain villages like La Fouly, Champex and Trient have returned to their low-key, familiar routines that have changed little over the decades.

But, from the perspective of someone who’s lingering a bit longer, I can’t help but find myself thinking, “Mon dieu! Where are you guys going?! We’re just getting warmed up!”

Here in the Swiss Alps, mountain running goes on. There are races every weekend until, well… until you need skis and climbing skins to move upslope. This is the home of ski mountaineering, after all, and as “ski mo” racers turn their eyes towards winter competitions, the running tilts still more vertical. Next weekend is Chandolin’s Double Vertical Kilometer, Vertic’alp comes along the ensuing weekend, followed a week later by the Fully, Switzerland Vertical Kilometer, known for being one of the fastest such courses in the world.

Perhaps no other event represents the spirit of alp fall trail racing, however, better than this past weekend’s Trail Dents du Midi, or “Trail DM.”

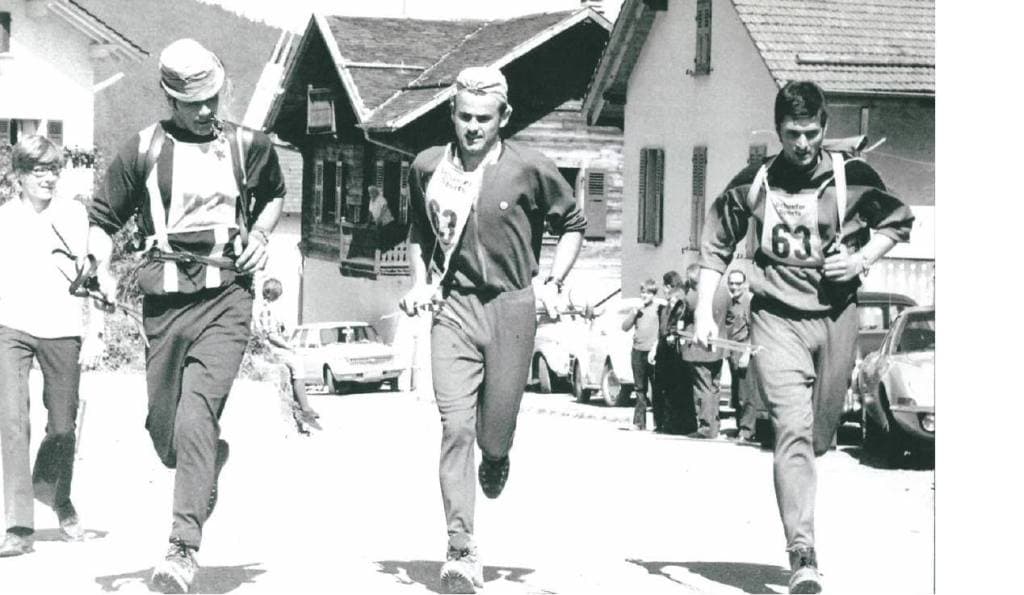

Trail Dents du Midi has a rich history. It is the oldest mountain race in Europe. (Nearby Sierre-Zinal, while more famous, is the oldest continuous race, as Trail DM lapsed between 2004 and 2010, when the original race committee disbanded.) Vérossaz resident Fernand Jordan, from the local Ski Club Daviaz, first conceived of the event. With brothers Raymond and Alexis, he gave the rugged course a test run in the summer of 1963. It passed– and the following year, a race was held around the range, beginning and ending in Vérossaz.

In the first decade that followed, local ski clubs, border guards, and Swiss and French military all participated in what was then a 44 km loop. Within a decade, a French military team from Grenoble had established the remarkably tough-to-beat record of 5:18:51. To this day, their time is downright impressive.

In recent years, an ambitious core of new volunteers has quickly been putting the race back on the map. Among them is local resident 43-year old Gil Caillet-Bois. Gil’s family has just a little bit of history with Trail DM, too– Gil is a past participant, and his father, Andre, has run the race a head-spinning 40 times, this year receiving a lifetime award for endurance about which most of us can only wistfully daydream.

Trail Dents-du-Midi isn’t yet on the annual radar of elite runners, as are races like Sierre-Zinal, Matterhorn Ultraks or the North Face Ultra du Mont Blanc. After all, there are no ISF Skyrunning points to be had, nor cash prizes. Instead, winners receive prizes very much in keeping with the spirit of the event: a trove of local cheeses, wines, breads and dried meats. What is an elite runner’s loss, accrues to the benefit of the spirit of the race.

This year, however, Trail DM made budding efforts to reach out to a wider trail running community. The race committee, in partnership with generous local businesses, recruited US runners Brian Tinder and Connie Gardner, both members of the Adidas Ultra team. Gardner took third woman overall, and Tinder second, after Swiss mountain runner Emmanuel “Manu” Vaudan, a mountain runner with a reputation for incredible uphill power. (Vaudan at one point held the world record for the vertical kilometer, with a time of 30:56 at Fully, in October, 2010.)

The 57 km long Trail DM course encircles the Dents du Midi range, a dramatic ridge of seven summits adjacent to the French border, topping out with the Haute Cime, at 3,257 meters. (Check out a video tour of the course, right here.) With 3,700 meters of climbing, there’s always a significant climb or descent looming. “A couple of times, I was looking up the course, and I saw someone scaling a cliff,” said Tinder. I thought, “No, that can’t be it. Where’s my route? But, every time, that was it.” Tinder’s no slouch about elevation gain, either—his native Arizona features thousands of feet of trail running climbs, and his new business, Arizona Running Adventures, takes European clients to the depths of the Grand Canyon and back up.

Ohio-based Gardner, meanwhile, has raced through in Europe– but generally on flatter courses in the Netherlands, France and Italy. She was humbled. “I’ve done 100 km races with faster times than this race. I was in over my head. It was a nightmare. I felt like I was at 14,000 feet. I was thinking, ‘My knees don’t hurt, my legs don’t hurt, my back isn’t bothering me…. And yet, I can’t move.’ My heart was going to explode. I would stop and try to get my heart rate down, regroup and go again. Then it would start over. I was thinking, ‘I’m going to finish this race, and then I’m going to focus on my golf game!’”

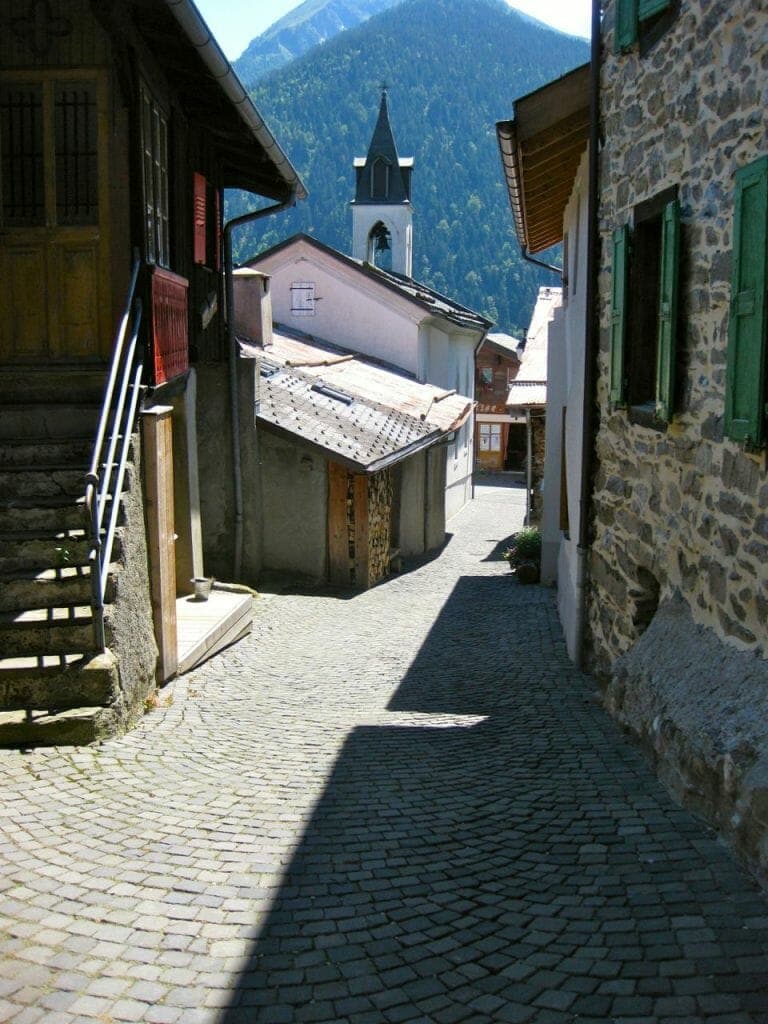

There are respites here and there along the course, though, with moments of relaxed cruising through alpine pastures. As I ran the course this year, in the citizen’s division, I dodged flocks of sheep, and ran my hands along the weathered hides of cows that stood, entirely unimpressed, at the side of the trail. There are more diversions en route, too, as the course passes through several small villages, stops at a remote mountain hotel, and passes by the Swiss Alpine Club’s classic, stone-built Cabane Susanfe.

For the American trail racer, Trail DM adds other elements not often seen at home—including chains during the exposed descent at Pas d’Encel. Bolted to the cliffside, they provide an extra measure of security against tumbling 1,500 feet to the valley below. (As I ran by, the guides cautioned me to walk not run, with the slightly-mischosen words, “More lightly! More lightly!”)

Will other American elite runners create a trend out of what Brian Tinder and Connie Gardner have started? Tinder believes so—for three reasons: the race’s unique history and challenging course, the region itself, and Champéry’s hospitality.

“This race is the oldest race in Europe, and it’s got great energy. Every moment has beautiful scenery, whether you’re running through a small village with cobblestone streets, or you’re going over a high, alpine pass with France in front of you and Switzerland behind,” said Tinder. “The course is amazing.”

“Then, there’s the town. Champéry is in a great area. There are wineries all around in the Rhône valley below, and places like the Matterhorn are just a day trip far away. Yet, it’s off the beaten path.

“Finally, the townspeople were incredible hosts. They loved having us here. These are some of the best people I’ve ever been around. They’re warm and welcoming.”

If the experiences of Gardner and Tinder are any indication, there will be more US runners coming, next year, as Trail DM’s organizing committee continues to develop the event.

For his part, Tinder hopes to return. He’s finished ultramarathons, only to be greeted by clapping from of a lone spectator. Trail DM was just slightly different. “I couldn’t believe the hundreds of people lining the finish along the small village main street, cheering you on for the finish. The place is very comforting in all respects.”