Pierre Gignoux: Making the World’s Best Ski Mountaineering Boots

Here in the Alps, as soon as the first snowflakes touch the pastures, trail runners stow their Salomons and Hokas and grab their ski mountaineering gear. As US ski mountaineering member and Run the Alps friend Grace Staberg spells out, skimo is some of the best trail running cross training there is.

Like those of us here in the Alps, if you’re a trail runner who turns to skimo for cross training, to mix it up a bit, to maintain winter fitness, and to give those trail running aches and pains a chance to heal after a long summer season – here’s a story for you!

Skimo, called Ski Alpi in France (short for Ski Alpinisme), has a long and rich history. And one part of that story takes place in a chalet in the little hamlet of Saint Martin d’Uriage, about a half hour from Grenoble, and ringed by mountains. Many people drive right past the modest building without noticing the small sign hanging on a post out front: Pierre Gignoux.

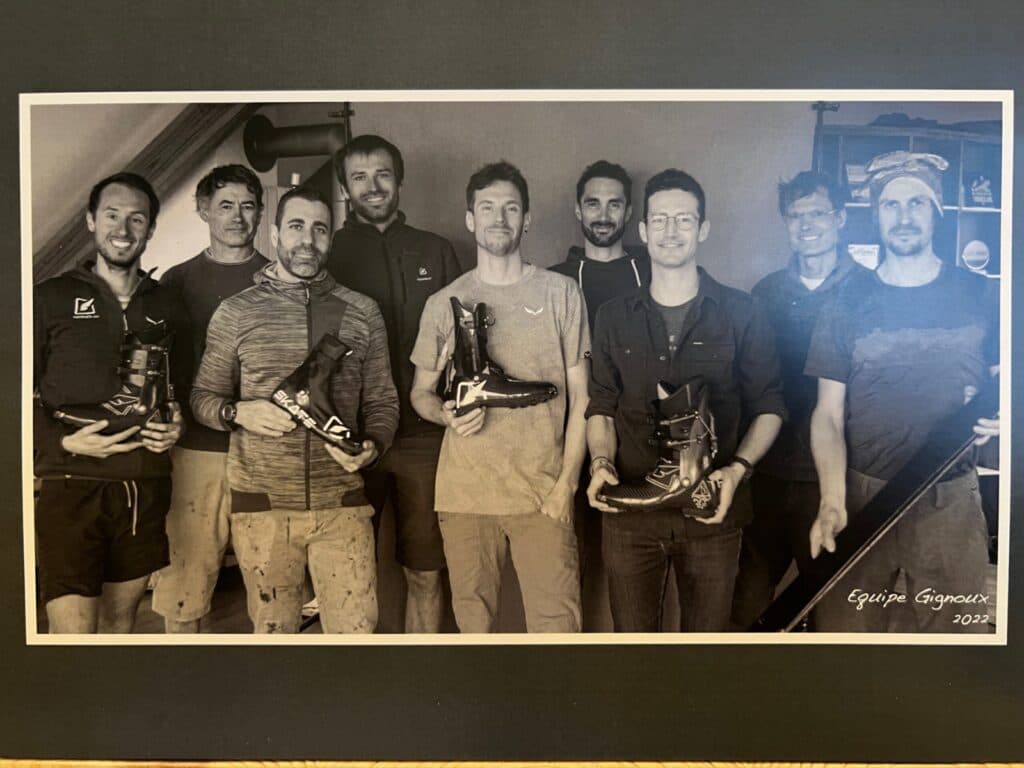

The company, named simply after its founder, makes what are widely considered to be the best ski mountaineering boots in the world. They’re carbon fiber, have a number of unique features, and only 600 pairs are made a year. And they’re all constructed inside the chalet on the side of the road in an Atelier Artisanal — an artisan’s workshop.

Cooking Resin in the Kitchen

A nordic skier initially, Pierre Gignoux’s introduction to skimo came in 1994, when a friend organized the TransMont-Blanc, a race that no longer exists. Gignoux went on to garner top results, including a win at the iconic Pierra-Menta as well as multiple second place finishes, and a string of gold medals in European World Cup races.

During that time– no less than thirty years ago– Pierre Gignoux was looking for a competitive advantage on the circuit. To reduce weight, he started tinkering with his boots. He removed parts and modified various components.

His work paid off right away. (And it’s a trend that continues to this day. Gignoux has also invented an improved binding system for locking boots into descent mode, which Dynafit has recently adopted through a new partnership with the company.)

In those early days, however, boot tinkering was really just a hobby. Gignoux would heat resin over his kitchen stove, an odiferous industrial process not normally happening in family kitchens. “My partner wasn’t very happy about it!”

But by 2002, he had a complete carbon fiber boot.

Still, he kept tinkering, and made improvements in weight and function step-by-step. Competitors started to take note. They began asking if they could buy their own pairs. “I reflected on it, and wondered if there was something here,” he says, modestly.

He proposed the idea of creating a skimo boot to his then employer, Rossignol, who initially said yes, but then had their doubts.

So, in 2006, with a notebook in hand, he started writing down names of people who wanted to buy a pair of his homemade boots. Before long, he had 30 names. And with that, in the basement of the chalet in which he lived, he and his first employee started making boots.

Is 700 Grams too Light?

Not everyone was happy about his lightweight, homemade boots though. The big boot companies, which were still manufacturing heavier boots, protested. Some of the objectors were members of the International Ski Mountaineering Federation (ISMF) that set the rules. And so a new regulation came into place: no boots would be allowed that were lighter than 900 grams each.

“I lost a big part of my business,” Gignoux says. That year, he made just 10 pairs. “It was anti-competitive. They were scared of me. It’s like that everywhere in business, I think.”

(The original: XP500. In 2006, ISMF did not allow a boot to weigh less than 900g, and by 2008, the XP 500 received the regional innovation price “Artinov.” From 2009, the XP500 was replaced by the XP 444 and the XP mountain, and more recently the Race 400 and Black.)

Racers who wore Gignoux’s boots had a trick up their sleeves, however. “They kept the shoes and put wheel weights on the cuffs, adding 200 grams of automotive wheel weights, so they would weigh 900 grams. They intentionally made their boots heavier.”

Even with the added weights, racers started to take note. Swiss ski mountaineer Florent Troillet won competitions with the weights, and everyone started to realize, says Gignoux, “It must be something else.” The other features, notably the freedom of movement and the rigidity of the carbon fiber, were helping the racers, too.

A year later, the regulation changed. Boot weight was lowered to 500 grams. Athletes who were part of the decision-making body at ISMF advocated for the change. The orders started coming in: 10 pairs, then 200 pairs, then more.

Pierre Gignoux Boots was launched.

Gignoux Today

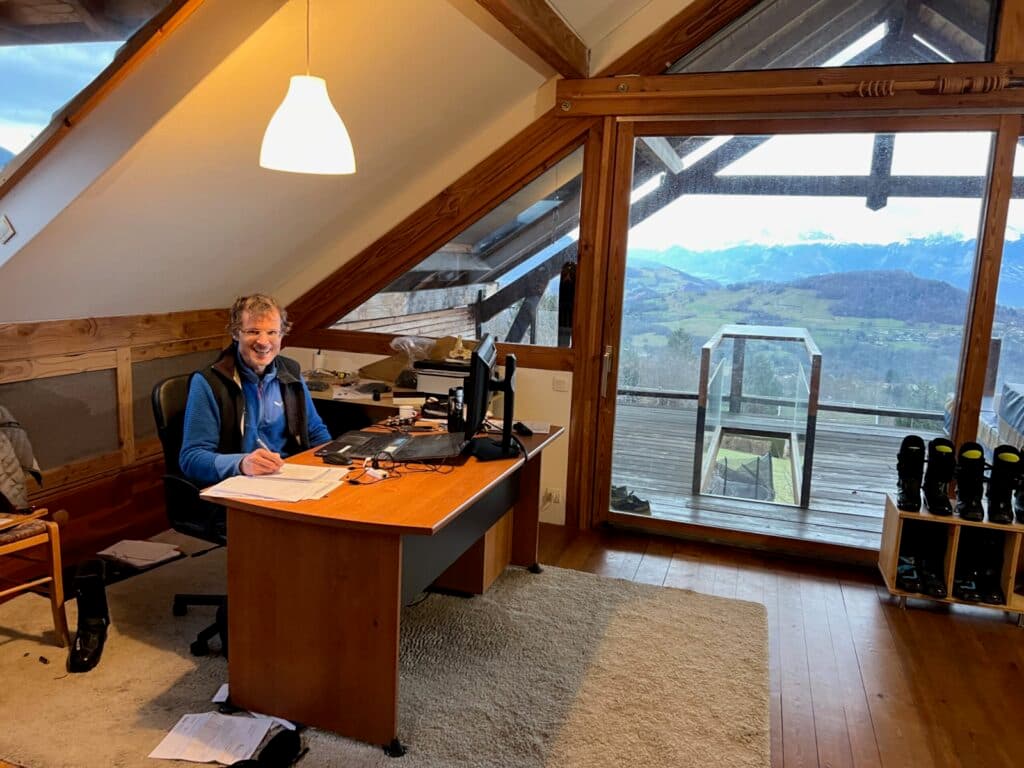

Today, Pierre Gignoux is 56 years old. He still makes boots in the same chalet in which he started. Only now the company has the entire building and he lives next door.

His upstairs office is also part showroom for customers who drop by the chalet to order boots. The large picture window looks across the valley on the Vercors range where Gignoux grew up cross country skiing.

Spanning one wall, there’s a watercolor of the Belledonne mountain range, where, two years ago, he skied and climbed over 21 summits in one push. That’s 10,300 meters of climbing. “Now I’m too old!” he protests. But he’s also clearly still in great shape.

There’s race memorabilia and boot prototypes scattered around.

The same as two decades ago, nearly all of the company’s business is direct orders, though they do partner with a few shops around the world. Half of their sales are in France, the rest scattered around the globe, including Italy, Spain, Austria and a growing business in the US, which now accounts for 25% of their orders. (In the US, you can find Pierre Gignoux boots at skimo.co and Cripple Creek Backcountry.)

There are six models available today, the lightest being the Race boot, which weighs just 560 grams. The Race Pro features an additional tightening feature, and there’s the multipurpose Mountain boot, and even a carbon fiber nordic skating boot. Recently, Gignoux has started making skimo bindings as well.

“Now, we’re selling more of the versatile Black and Mountain models,” Gignoux notes the growth in the popularity of backcountry skiing.

Sales are mostly word of mouth. “That’s how it works for us,” Gignoux says. “People love our boots and they tell others. I do some marketing, but very little. I think I’m not particularly good at marketing.” Company staff go to four events each winter. The factory has the good fortune of having the Chamrousse ski area just down the road. “Our sign outside works pretty well,” Gignoux says. It’s a marketing strategy from about 100 years ago, and that seems just fine with Gignoux.

Le Bilan Carbone: Measuring Carbon Impact

“For me, it’s perfect the way it is, with 12 employees,” Gignoux says about the company today. “I’m not interested in growing. We’re in a niche market, and that works well for us. If we added more employees, we’d have to move to an industrial location, and I’m just not interested in that.”

Instead of the endless growth that so many company leaders seek, Gignoux is focussed more on two aspects of quality – the quality of his product and quality of life for his team. “We’re trying to put things in place for a four-day work week,” he says. “We want to improve the quality of life and work. And always, we are working on improving the quality of our boots, their durability, and our service. We’re not really interested in growing. That’s just not our style.” The main goal, he says, “is for us to respect the mountain environment.”

The company is trying hard to lower their carbon impact, too. Not much can be done to lower the carbon impact of the materials they purchase from their suppliers, but what they can focus on is what happens at their workshop. They’ve installed solar panels on the roof, and they’ve looked at the impact of their employees during their commutes to work. “I’m trying to incentivize them to car share, or to come by bike, or to live closer to work. Of course, I live very close by.” Gignoux laughs and points out the window to his home. “It’s not easy to make these changes, but we need to do it.”

Pierre Gignoux is also a 1% for the Planet member, supporting the following associations: Alternatiba (climate and social justice movement), Les amis de la terre (environment, climate and human rights), Hop (stop planned obsolescence, fight against waste), Mountain Wilderness (mountain protection association), Reporterre (ecology media), and 82-4000 Solidaire (sharing mountaineering with the most deprived).

What does the future hold for the skimo boots that are now iconic around the world? “We’re working on a new system for next year’s boots,” he hints. “But we’re not quite ready to announce it yet.” Additional improvements are focused on durability. “It’s really important that the boots last as long as our customers want to use them.”

These days, Pierre Gignoux no longer races competitively, but his time out of the office is still spent where he loves it most – in the mountains.

For More Information:

Skimo for Trail Runners by Grace Staberg

International Ski Mountaineering Federation