The Persistence of Memory

Editor’s Note:

A long-time competitive trail runner from San Rafael, California, Victor Ballesteros ran Italy’s Tor Des Géants this past summer. “TDG” is, in many respects, beyond comprehension. The 330km race starts and finishes in Courmayeur, on the south side of Mont Blanc. It includes over 80,000 feet of climbing and descending.

Victor is no stranger to this demanding race format, with a second-place finish at the inaugural Tahoe 200 and fourth-fastest supported Fastest Known Time on the Tahoe Rim Trail.

Run the Alps had the pleasure of hosting Victor, his wife Jena, and friend David at our home in Chamonix, France, after TDG. Victor, we should note, seemed happy – and tired. Okay… very tired.

Victor’s exploits and adventures have led him to create Victory Sportdesign, makers of Victory Bags, super-organized and functional all-purpose gear bags.

His story of the 2018 TDG is both touching and remarkable. We’re delighted to share it here.

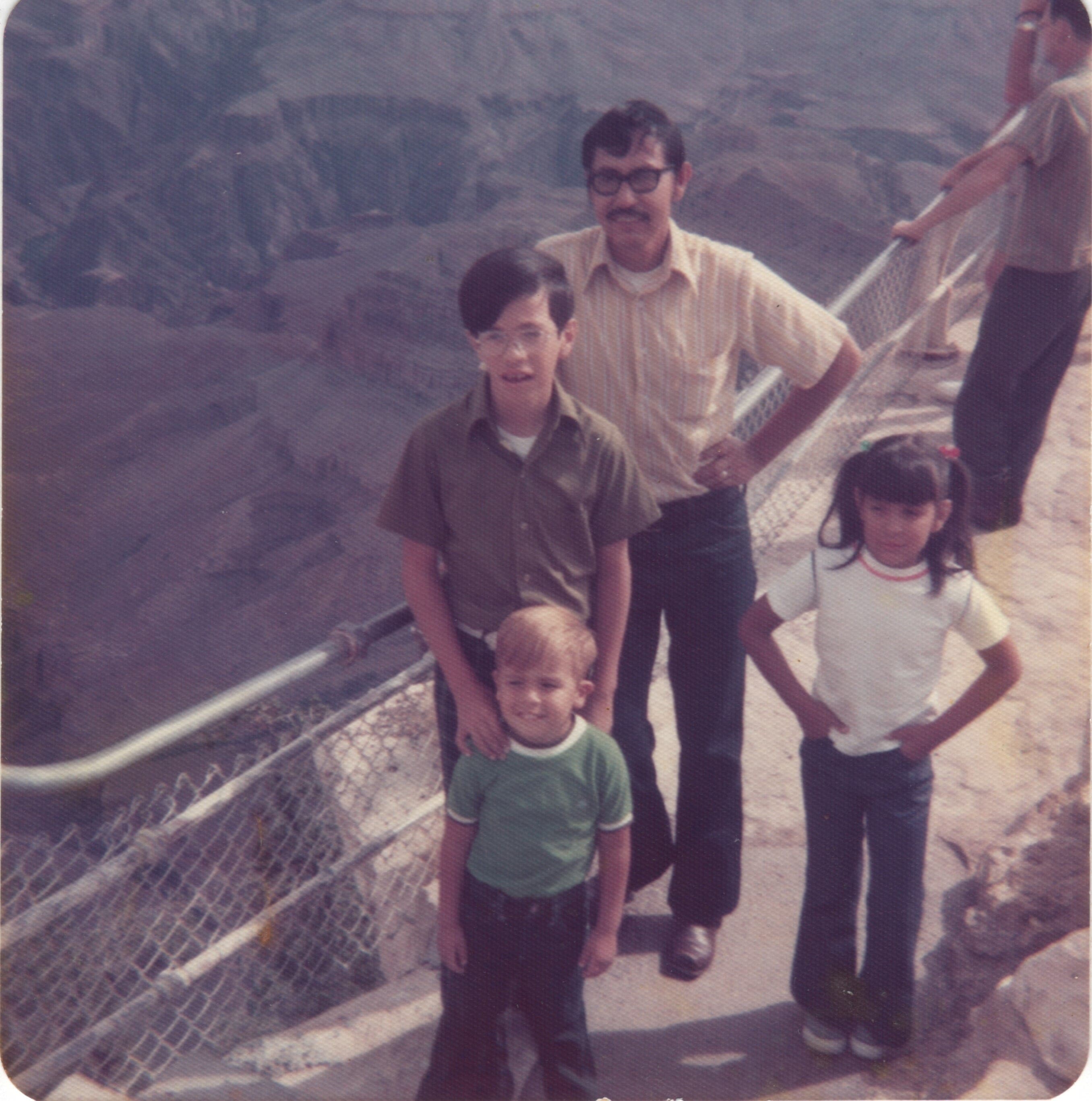

“Walk 100 yards and then I’ll carry you on my back for 100.” I shuffle my feet counting “1, 2, 3…” “No, no, no… a yard… this is a yard”, my father says, as he throws his foot out in full adult stride. Compared to my tired 8 year old gait, it’s a giant’s step. I try to adjust my count, desperate and eager for the brief hoist upon his back. After what seems like forever, the next set is marked by the rhythm of his breath and steady drop of foot to trail.

After a long anxiety-filled day of travel, I arrive alone in Aosta, Italy. The following days are spent sleeping, acclimating to the time and place, and waiting for my wife Jena and friend David to arrive. I look over gear and maps, thinking about the last time I made this journey three years before. The journey is the Tor Des Géants, a 206 mile behemoth of a footrace with an astounding 80,000ft of climbing that circumnavigates the Aosta Valley in Italy’s Northeastern Alps. The name, often shortened to TDG or Tor, is a regional mash-up of French and Italian meaning ‘Road of the Giants’. Three years ago I felt like a giant going into it. My will and strength had been solid, but these mountains demanded more respect than I gave. Rain, cold, and snow chewed me to shreds, swallowed me up and spit me out three times over. Ultimately the race was cancelled, but not before the monster “Tor” had laid my crumpled body down in the small hamlet of Niel, mile 120, 10 hours before the official cancellation announcement. Now, as I sit alone waiting, an entirely different spectre needles at me. I know partially what lies ahead, yet the other half remains a mystery. My memory serves as the only tool I have to put my thoughts, hopes and fears in place. Something blocks my spirit, and I can’t shake that spectre. Unfortunately, no matter how my memory plays out, fear permeates every corner, casting long, dark, and gut-twisting shadows.

“I’m tired. I can’t make it.”

“We’re almost there,” my dad answers back.

Never one to dumb down conversation or speak to me like a child, he begins to tell me stories about growing up in Mexico City, and his boarding school days. He goes on about exploring the city streets and encountering odd and intriguing people, and of classmates that made him laugh, and those that left him wondering about their fate. Listening to his tales gives a lift to my feet. My waning energy fills back up, and suddenly I realize I’ve walked way more than 100 yards. “Look!” He stops just ahead of me looking out over a high granite ledge onto the valley floor below. “See… we made it.” He sits down with his legs hanging over the edge of the dangerously long drop. I sit next to him. The last bit of climb to the top of Yosemite’s Half Dome is a bit farther up the trail. “Wait here,” he tells me. “I’m going to run up and check it out.” 15 minutes pass as I sit there alone, feet still dangling, oblivious to the fact that we hiked ahead of my mom, brother and sister, and went this far without telling them. My dad reappears through the bushes. “Ok, we’d better go back before it gets dark.”

The heat of the Italian morning sun beats down on Courmayeur’s town center, packed with 1,000 euro-clad “Trailers” (which is what they call those who make the trek) ready to embark on 1,000 different journeys. I had parted with Jena and David, happy that they were there and eager to see them again. As the countdown begins, Peter Frampton’s voice rings out over the surrounding speakers: “Do you feel like I do?!” Before I can mentally assess an answer, the announcer’s voice follows with a booming, “Do you feel like I do, Tor Des Géants?!!” It’s a European moment that lingers with me… for days. He works the crowd into a round of cheers. I might have answered the call confidently, had I not lost my voice from a cough that began two days earlier. Jena thinks it’s nerves. I try not to think about it. My mind searches for a moment of focus before the frenzy of the start. The countdown drops with a steady chant. I touch the ground trying to draw some strength from the universe. Something in my spirit still feels off. And with that, the race begins.

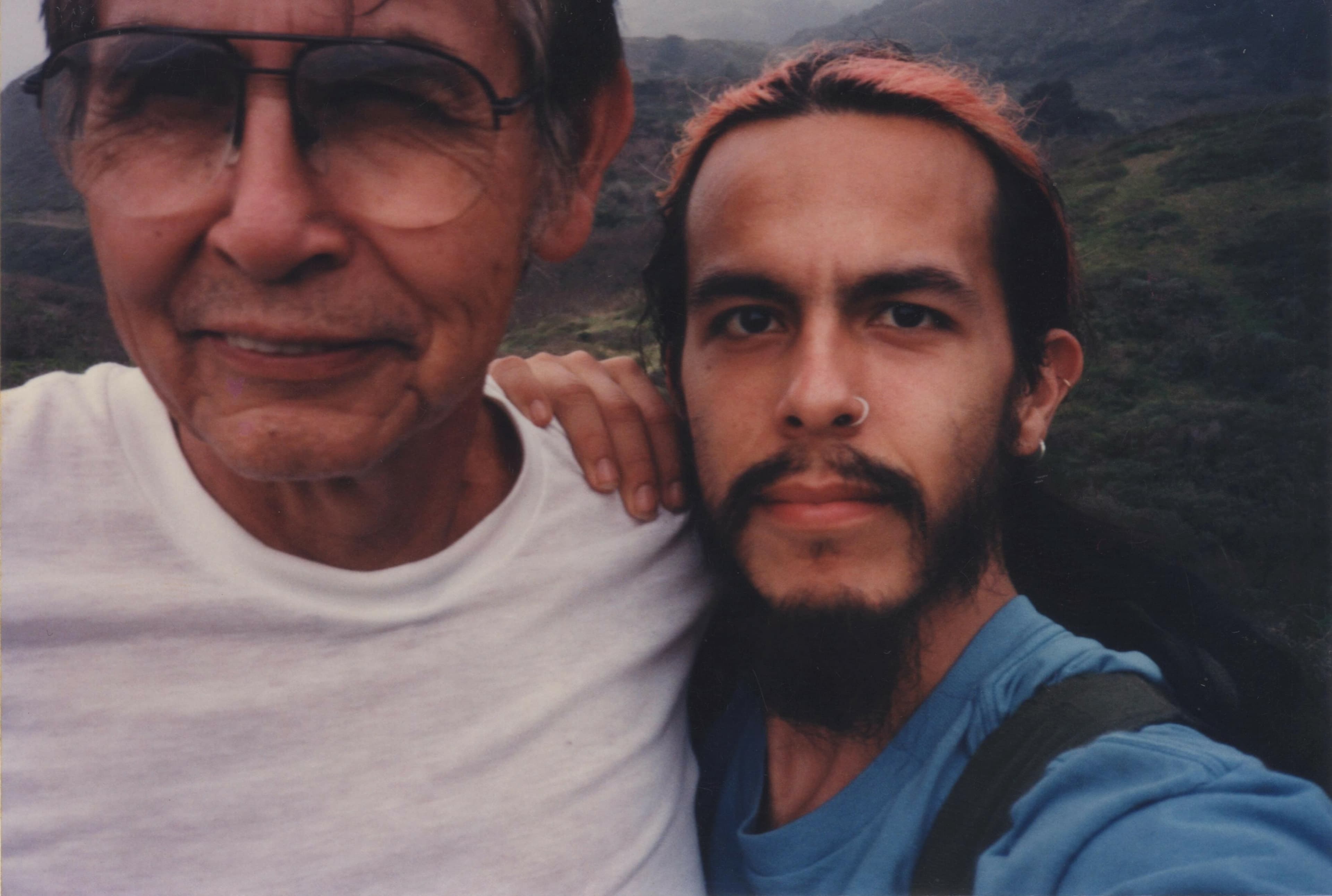

My dad moved fast down the trail. Never one to dilly-dally, he’s a solid build of forward motion. Slicing him up into a perfect dad pie, you’d find a disciplined ex-soldier, an athlete, a free-spirited adventurer, a joker, and a brilliant tactician. He has also been stubborn, vain, and incredibly selfish. The one quality that bound these various elements together to complete the man named Eduardo Ballesteros, is the one not many were privy to: His love.

Earlier in the year, as I planned my triumphant return to the mountains of Northern Italy, my mom calls to let me know that dad’s in the hospital. For the last three years, we know his mind and physical capacities are declining. It’s dementia, but its progression is slow and inconsistent in its development. I keep focused on day-to-day routines, as my mom assures me that all is well, but this call is different. “Dad’s taken a bad fall – we’re at the hospital.” As usual, she makes it sound serious, yet benign. When I arrive, I’m slammed by the sudden depth of his (and my mom’s) situation. My dad’s mind sways in and out of darkness. His speech is garbled and incoherent. His memories, save his recognition of us, are shadows. The doctors begin talking about end-of-life decisions. I rail at myself for not seeing this moment sooner. My mom needs every bit of help she can get, and I try to fill the gaps. She cries when I hold her, unable to unlock tears of my own. Immediately, everything seems so inconsequential. TDG is a frivolous endeavor. Running makes no sense. I shift my focus to help my folks as much as I can, yet somehow I still remain connected to being in Italy by September. The months leading up are fraught with physical issues, doubt, apathy and depression. If a workout begins, it rarely gets finished. Drinking becomes an easy way to numb nerve endings at day’s end. Regardless, the cogs keep turning, and eventually I realize that the wheels aren’t stopping. Jena does all she can to help me move forward. Like a bad college student, I cram for finals with 15,000-foot climbing workouts that confuse and make no sense to anyone. I keep my plans secretive, because I fear the possibility of another failure. My spirit is blocked, and I’m lost in a tailspin trying to understand the path before me. Before I leave, I sit quietly with my dad. I tell him about where I’m going. He gives no response. I simplify it and say, “Dad, I’m going away to climb up and down big mountains.” His eyes brighten up as he responds, “Oh?!” I gently touch his arm and tell him, “I love you Dad.” He looks at me and says, “I love you too.”

The Alps are another planet. They’re immense, relentless, and often ridiculously dangerous. The weather forecast is surprisingly hot. I laugh to myself. Back in California, June through August baked in a heat wave. I rebelled against training in it because I doubted the conditions on race week would ever come close. Tor 1; Victor 0. Three years ago, weather was an issue and I moved too aggressively. This time, I focus on what the terrain gives me. I move slower to save my strength, and take caution to care for myself in the exposed heat of the day. Much of the trail is made up of massive stone steps, more suited for giants. Road of the Giants, I muse. Navigating the terrain pushes my energy levels into the yellow zone. Beginning on the second night, I plan on sleeping for a half hour or so. My cough grows in agitation, but I continue to ignore it. Then I see Jena and David – my life-savers. They pop up at moments when I need them most. From day into night, into day again, all I think about is where I am. My place in competition means nothing, my time stays tucked away in a pocket. I pass Trailers, and am passed by many more. I whisper to myself, “Relax, this is going to be a long trip.”

The long hike back down to Happy Isles on the valley floor is now light and effortless. How can it not be, heading to a place with a name like Happy Isles? We skip like giants taking large granite steps two at a time. I must be exhausted, but my father’s company continues to fill me with life. Even though it’s getting late, we stop to take in things we missed on the way up. My dad makes up intricate stories about heartbroken love and tragic waterfall leaps and long lost family connections to John Muir. At a certain point his smile beams as he insists, “It’s true!” I nod and laugh. The sun is setting quickly. Far below on the valley floor, my mom awaits, not-so-happy at the Isles. As should usually be the case, eight year olds are often not in the know about mom and dads’ communication, or lack thereof. With no light to find our way, save that of the waning moon, two rangers appear. “Are you Ed Ballesteros?” they call up from the trail. “Yes!?” my dad hollers back. “Good, we were sent to look for you both, and your wife is not too happy about it.”

Another long alpine night approaches. My mind and energy start to drift. I push myself through the last sections of trail I remember, and start to grow frustrated that I remember none of it. An ingested surge of Five Hour Energy propels me forward. Excitedly, I think about getting to Niel and moving beyond into the unknown. Climbing high into the dark, I look back to realize how ridiculously dangerous the ascent is. Whose idea was it send us this way? With the slightest lean back, beyond better judgment and/or fatigue, the difference between life and injury (if not death) is inches. One Col (the highest point of a climb before the descent) follows another, and another, and another. The long drop into every aid station and Rifugio, or mountain cabin, begins to follow a pattern of never-ending approach. The lights of my certain destination are like phantom beacons floating further away from me. “Do you, feel like I do!?” Peter sings to me. The guitar riff repeats endlessly as I wonder, “Do I?” Just as I begin to doubt the existence of any relief, the flags and banners of an official TOR aid station appear. I’ve arrived at Niel. In the dark, Jena and David don’t recognize me until I’m directly upon them. I’m thinking I should sleep for an hour, but don’t say anything, with the intent of moving on. It’s a mistake. Tor 2; Victor 0. Jena tapes up my sore muscles as I quickly eat. In the bathroom, I notice subtle cartoons playing in the design of the floor. Thankfully, it’s the only way I ever hallucinate, and for the moment, it’s mildly distracting. With haste, I hug Jena and David then disappear back into the dark.

The “trail” now becomes a hazy surreal vision that I don’t really need or want. Long stone slabs and short walls on both sides create a rough, ancient path that evaporates into the night. The novelty of it quickly wears off as the path goes on, and on, and on… I stop to let everything sink in. With a deep breath, I start coughing violently. The cough turns into dry heaves. The only thing I can do to stop it is breathe in through my nose, which I never do. It’s so novel and foreign that I start to question it, and wonder if it’s a sign… a bad sign. Within minutes I realize how tired I am, but I’m not turning back. A headlamp passes me, and for once I hang onto its forward movement. Together we make the climb in silence. The following forever descent into Gressoney is marked by only two thoughts: this is supposed to be the hardest part and it’s now over; and I really need to sleep.

My dad and I finish the final descent in silence. I could make out the silhouette of my mom standing at the trail head. As I approach her, she gently hugs me. Her voice is soft, “Are you okay?” I smile and nod. She sternly looks at my dad and says nothing. They had a graceful way of handling confrontation in private. I never asked my dad how he explained it to her, but the truth was simple: What was supposed to be a short family hike to Vernal falls turned into him and me going a little further, and then with no word to anyone, his oft impulsive idea, “Let’s go to the top!” Forget that it’s a 17 mile round trip, you only have six hours of daylight, and you’re only eight years old. Yes, my mom was rightfully pissed, and I’m sure my dad received a good what’s-what from her. In her way, she never had a problem letting you know what was on her mind and how she felt. That was one of the many parental divides between them. She never failed to express her love, champion your goals and dreams, and simply be there when you needed. Her support was forever constant and unconditional. On the other hand, my dad’s ability to connect in the same way was far less expressed. The one place he opened up the most was out in nature. The wilder it was, the more he shined, and the greater the adventure. For whatever reason, my older brother and sister never opted in to his crazy ways. To me, the twinkle in his eye when there was a secret trail to follow, or a spooky dilapidated cabin to explore was contagious. It was the way he knew how to share who he was, and when that train came roaring into town, you jumped on and held tight with all you had.

I sit at a table in Gressoney’s sport complex staring into space, and whisper to Jena, “I’m not sure about doing this anymore.” I look solidly at David and grumble, as if I were scolding a little boy, “Don’t ever do this race!” Jena’s voice is sweet, confident and comforting, but I can’t make out the words. My head nods. “I’m falling asleep” I tell her. “Let me sleep for three hours. Stay with me and wake me up.” We retreat into a large, quiet, dimly lit room. I close my eyes, but the continuous aggravation of fluid and wheezing in my upper chest forces an incessant clearing of my throat followed by a harsh cough. What was three hours feels like two minutes. “One more hour” I plead. I lay my head down, only to come back up. “It’s time to go.” Jena’s voice fills my ears like a disjointed echo. I stare at the ground unable to move. “One more hour, and that’s it.” With a heavy sigh, she lets me put my head down. Again, she wakes me, and finally, I stand up and leave.

Unlike everything else on this trek, the path leaving town is remarkably flat. I think about running, but my body settles for a fast walk. Suddenly another Trailer comes up from behind and passes. My effort appears to be the same as theirs, but soon they’re gone and out of sight! I mumble to myself, “Dang! These Europeans walk fast.” Through a few directional mishaps, Jena and David miss me over the next 30 miles. It’s fine. I’m not concerned and thankfully my energy is up. I reach the top of Col di Nana, which entertainingly makes me keep saying, “Banana.” The whole time I’ve taken very few photos, when out of nowhere appear a group of ibex. They posture before me like a postcard, or Nat Geo photo of the year. I take out my phone and turn it on. Just as I aim the lens, they run off into the mist. I smile to myself and think, “Of course.” I put the phone away as they casually walk right back into place. “Really?” I shake my head. I pull the camera back out and slowly take aim as they quickly disappear again. I’m convinced, as I smile and say “jerks”, that I hear the distant sound of ibex laughing. The evening begins to settle into another night.

As much as my dads’ adventures drew us together, I’m surprised that some of them didn’t kill us. In the throes of it all I learned things about him that I never would have, if I hadn’t taken up his crazy charges. As I got older, that bond allowed me to be more confident and comfortable with asking him about who he really was. It also allowed him to see me for who I was, and who I wanted to be. I only heard him say he was proud of me a handful of times in my life, but that didn’t matter. “I love you” was the golden unicorn, and those words were expressed enough times to make me feel like we understood each other.

The long drop down into the town of Valtournenche pounds me into the ground. I’m resigned to sleeping another two hours, hoping it’ll reboot my system. Jena says she has something for my cough, but thinks it’s more of a weird tasting licorice candy than medicine. I take it. Anything at this point is up for sale. I’ll suck on rocks if it’ll help. Again, I thank them and head off into the early darkness of dawn. I cough and pause, pause and cough. With each violent thrust, peanut sized globs start shooting out of my mouth. Intrigued, I catch one in my hand and notice blood on it. Upon discarding my tiny unholy offspring, I tuck my concern away along with my headlamp.

A small Rifugio emerges as the morning sun begins to illuminate the sky. I step in, just so the officials there can record my number. I see tea and think, “Ok, I’ll pour myself some hot tea.” Really, I know I need to move on. Instead, I finish my cup and ask for an hour nap upstairs. I close my eyes and think to myself, I’m a full day behind my goal of finishing. Upon waking up, the outlandish concept of that sinks in as I force myself to get back out onto the trail. Trying to conjure thoughts and images that might propel me forward, I think of an eight year old me, riding on my dads’ shoulders, when the image disintegrates by the intrusion of Peter’s voice, “Do you, feel like I DO!?” The guitar riff plays out in time to the taps of my broken-on-one-tip-and-now-badly-worn-down-lopsided poles. I guess if that’s all I have, so be it.

I try to think about something strong to push me forward: Jena, David, our pups at home, my friends, my family, my mom, my dad. I try to fill my soul, but keep coming up empty. Even the glorious beauty that surrounds me fails to penetrate the void.

I arrive in Oyace to the cheers of my only light. Jena and David escort me into the small ‘aid station’ hall where I proceed straight to a bed. I tell Jena, “Give me three hours, then get me out of here.” Unlike all the other sleep areas, this place is loud and bright. Despite it all, I sleep like a log convinced it’s the only way for me to find strength. Three hours later, determined to charge my way to the finish, I begin repeating to myself, “This is my last night. This is my last night.” The light from my headlamp catches the reflection of course flags leading up to oblivion. I repeat, “This is my last night.” I breathe in through my nose and find a solid rhythm. The intensity of working the flow of oxygen, again, makes me think that I’m going to pass out. To take my mind off of it, I start popping the sweet throat lozenges. They’re not bad.

It isn’t long before the sun begins to rise, and I start repeating to myself, “This is my last day.” After what seems like another forever, I stop anticipating the arrival of the aid station, and in that moment Jena and David appear on the fire road. We shuffle together into the aid station at Saint-Rhemy, where I quickly check-in and leave. It’s the last time we’ll see each other until the end. I predict that I’ll be there by 4pm, and charge off into the warm morning sun. Tor 2; Victor 1.

The company I share on the trail now consists of a variety of shapes, ages and genders. My stupid ego might have told me that I was slacking and not performing to my potential, but it doesn’t. I know I’m amongst incredible people, as far as I can tell… I notice an older man who now appears intermittently. He looks like Anthony Hopkins. Not “The Remains of the Day” Anthony, but more like “Thor – The Dark World” Anthony. I begin to notice him leapfrogging with me. I pass him decisively, certain that I’ve seen him for the last time. The climb to the final Col before the descent to the finish in Courmayeur rises before me. Two more Rifugi also remain.

To my dismay, the energy of my nighttime charge begins to crumble into a crawl. After another eternity, I finally enter the second to last mountain inn, and collapse at an empty table. My voice is so gone that I can only whisper “Zuppa per favore?” The spoon is barely to my lips when my head begins to nod. I stare at the bowl in disbelief. Another nap?! Shit. Fine… a half hour. What’s another half hour in the scope of it all? At the wake-up call, I emerge from a dream I can’t remember, yet happy that I know I dreamt. As I suit up to leave, Anthony appears and starts off for the trail. I’ve hardly pulled myself together, but damned if I’m going to let him beat me to the finish. Odin or no Odin; like all the other times before, he soon becomes a dot far behind me in the distance.

I crest the last Col: Col Malatra, and shuffle my way down to a vast open plateau. Scanning ahead, I try to make sense of where my path is leading. Following four dots ahead of me, a fifth one appears. I’m confused and then shocked. What?! What?! Anthony!? What the hell!?!?! How did he?!?!? I’m now incensed. What kind of path is he cutting? And now I’m paranoid. How many more have done the same thing? With no time to dwell, I pass him again and move on, but the damage still clings to me. The trail makes a familiar shift from exposed scree to forest. The path starts to roll, and the Mont Blanc massif, towering over the finish in Courmayeur, finally appears. It’s way past 4 pm. It’ll be dark soon. The outskirts of the town are far below. I think about shuffling, but can’t. I want to move quicker, but can’t. Three guys pass me and I decide to sit down on a rock and text Jena: Ok I’m back in trouble again, I don’t know what’s going on. Still haven’t made it to the last Rifugio. She replies: Do you want to talk? If not, no worries. Just thought maybe if you heard my love and support it would help give you propulsion. You can do this… We’re rooting for you!

Not knowing how close I was, or why I couldn’t move was killing me. Tor 3; Victor 1??? NO! Having nothing left to eat but the sweet throat lozenges, I take them all from the bag and shove the handful in my mouth. I whisper to myself, “Screw you lack of energy!” as I stand up and start moving forward. My lopsided poles ram into the trail with steady rhythm. “Damn poles, all lopsided, think you can throw me off?! Screw you!” With each step my voice grows a little louder. “Screw this trail and its never-ending climbs and descents. Screw you, Courmayeur, way down there like I’m never going to make it off this mountain.” My energy starts to change. “Screw you tired body, trying to tell me that I’m done! And you, cough, trying to slow me down. I’m breathing through my nose. What you gonna do about that?!” My pace begins to match with that of my anger. “You can’t beat me TDG! I’m going to start running, and I’m not going to stop!” The tips of my poles tap less and less on the ground. “Screw you Peter Frampton, I DON’T know how you feel… but I like the guitar riff.” My voice is now completely shot and reduced to a raspy buzz. “Screw you long-ass night! I’m getting to the end of this without turning on my headlamp!!” I see one of the guys ahead of me as I start to close the gap between us. “Screw you Anthony Hopkins, cutting the course like it’s no big deal!!!” I’m now running, when I start to feel the rhythm of his breath and steady drop of foot to trail… “Fuck you dementia, for taking him from me, himself, and the world!!! Screw everything that takes those we love from us. Screw this world for the things I can’t change. Screw everything for trying to be strong and not letting myself cry. Screw it all!!!”

I arrive at the last checkpoint along with the three guys who had passed me. I’m told it’s an hour to the bottom. I think not, and begin to sprint. My feet feel light, like I’m floating. With every step, the rhythm of his breath and steady drop of foot to trail is all I hear. Tears roll down my cheeks, and I let them flow. The more they flow, the lighter I become.

I can see and feel the sky transform, along with the trees and trail into the summer memory of so long ago. The back of his strong shoulders are before me and I hold on. The rhythm of my breath and steady drop of foot to trail carry me through to the outskirts of town. People walking on the sidewalks and sitting at cafes cheer me on as I run down the street: “Allez, Allez, Allez!” The greatest cheer comes from Jena and David when they see me. I can’t hold back my tears, and I can’t slow down. She tells me, as she matches my cadence to the finish, “It’s okay to walk!” I reply, “I just want to be done.” Ten seconds later it’s all over and I’m sitting with them on a bench and smiling like the past five days never even happened. The last rays of sunlight start to set. Tor 2; Victor 2.

The warm California sun drops on the horizon as I try to convince my dad to move his chair into the shade. He gets agitated and stays put, but after a while gets up and begins to walk the perimeter of the back yard. His balance is choppy and uneven, so I trail close behind. It’s hard not to notice how small and frail his body has become, when suddenly he stops and flexes his arms to show how strong he is. He’s still a clown. We pause at the gate that leads out to the front yard and street. I can tell he wants to leave and walk around the neighborhood, but it’s getting dark, and maneuvering the street at night is sketchy. I smile and tell him, “Walk 100 yards and then I’ll carry you on my back for 100. That’s the only way we can do it.” He pauses for a brief second, looking out past the street to the far off golden hills. My words serve only as a slight distraction. It doesn’t bother me; I’m happy to see he’s no longer thinking about leaving. We stand there in silence, before I decide to tell him about where I’ve been and everything that happened. Again, my words elicit no connected response. I simplify it and tell him, “I climbed big mountains and thought of you.” He answers definitively, “Yeah,” like it’s an obvious given. I smile and nod my head, “Yeah.” With a deep sigh, my hand rests upon his shoulder as I tell him, “I love you.” His eyes remain fixed on the horizon.

“Good, I love you too.”